ICML 2025 AI4Science Contribution Report

The International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) 2025 took place in Vancouver from July 13th to 19th. Most of the contributors in this field gathered for a week to present and discuss the state-of-the-art in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning across various fields. If we were to categorize the different topics at the conference, the main titles would be Optimization, Algorithms (mostly Reinforcement Learning), LLMs & Transformers, and Applications (in areas like biology, chemistry, classification, diffusion, etc.).

What is AI4Science?

In this article, we will focus on what happened in the field of AI for Science at ICML. First, let’s talk about the term “AI for Science.” It mostly refers to how we can apply data-driven methods like deep learning to the forecasting, modeling, parameter tuning, and controlling of physical phenomena that are often difficult to solve analytically with pure math. This is not a new field; humans have been interpreting the world around them via gathered data and observation since the first civilizations and have tried to find patterns and logical explanations for nature. The novelty here is this recently capable, data-based tool — machine learning — for interpreting these kinds of data and finding sophisticated patterns from a massive amount of observations.

Until now, we’ve seen how ML is good at tasks like natural language processing, image generation, and classification. However, when tasked with, for example, forecasting the motion of water flow based on exact physical features, these models can lack accuracy and fail to follow the precise physics behind the phenomenon. This is where we define the field of AI for Science, or Scientific Machine Learning. Different communities from various departments like mathematics, computer science, natural science, and engineering are conducting interdisciplinary research to leverage machine learning approaches, solve the aforementioned problems, and harness the benefits of AI’s speed, accuracy, and intelligence.

AI4Science at ICML2025

At the very beginning of this section, let’s list all the papers (say, most of them; I may have missed some!) that were presented at the ICML2025:

| Paper Name | First Author | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| Linearization Turns Neural Operators into Function-Valued Gaussian Processes | Emilia Magnani | Neural Operators |

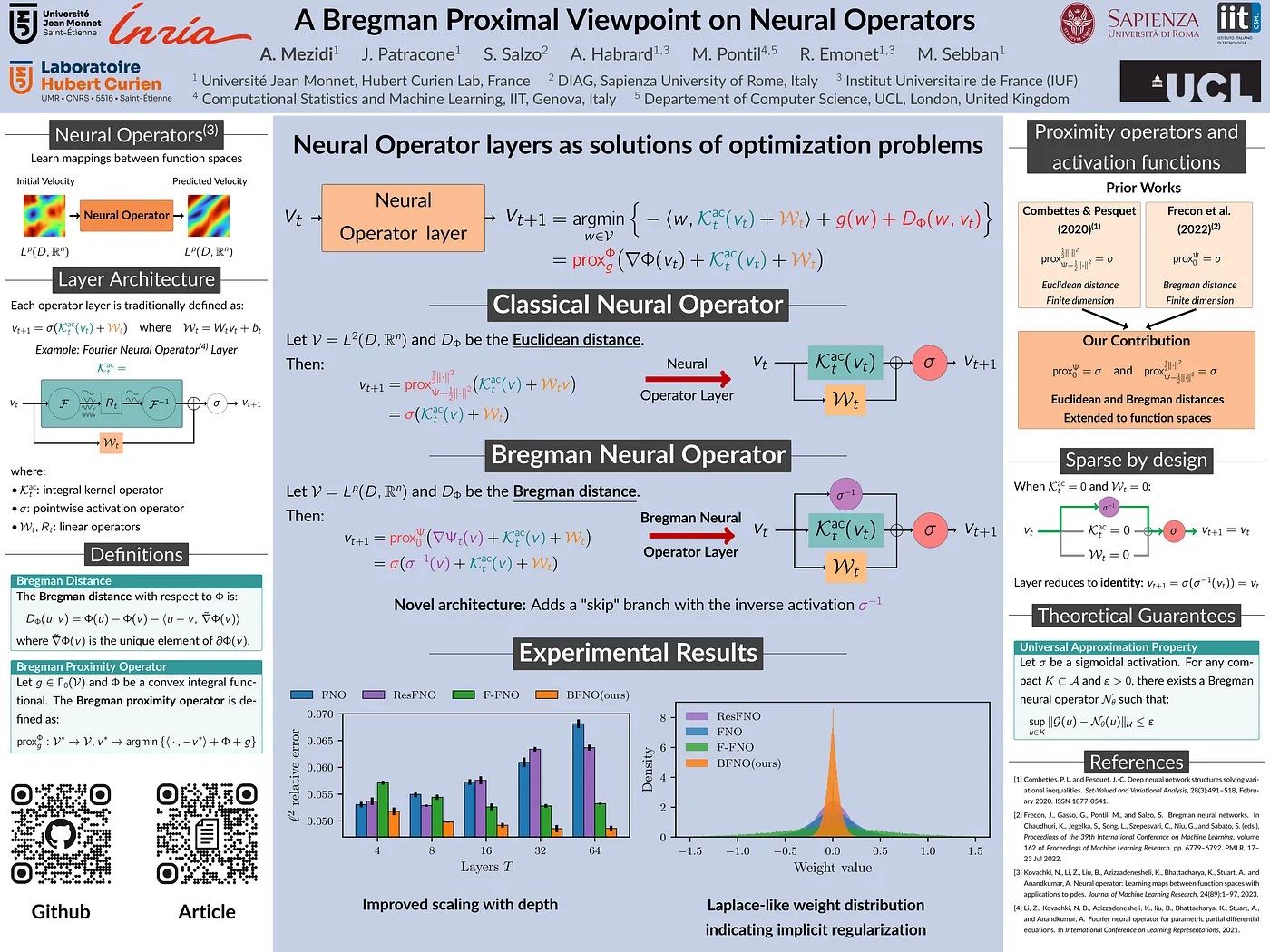

| A Bregman Proximal Viewpoint on Neural Operators | Abdel-Rahim Mezidi | Neural Operators |

| Maximum Update Parametrization and Zero-Shot Hyperparameter Transfer for Fourier Neural Operators | Shanda Li | Neural Operators |

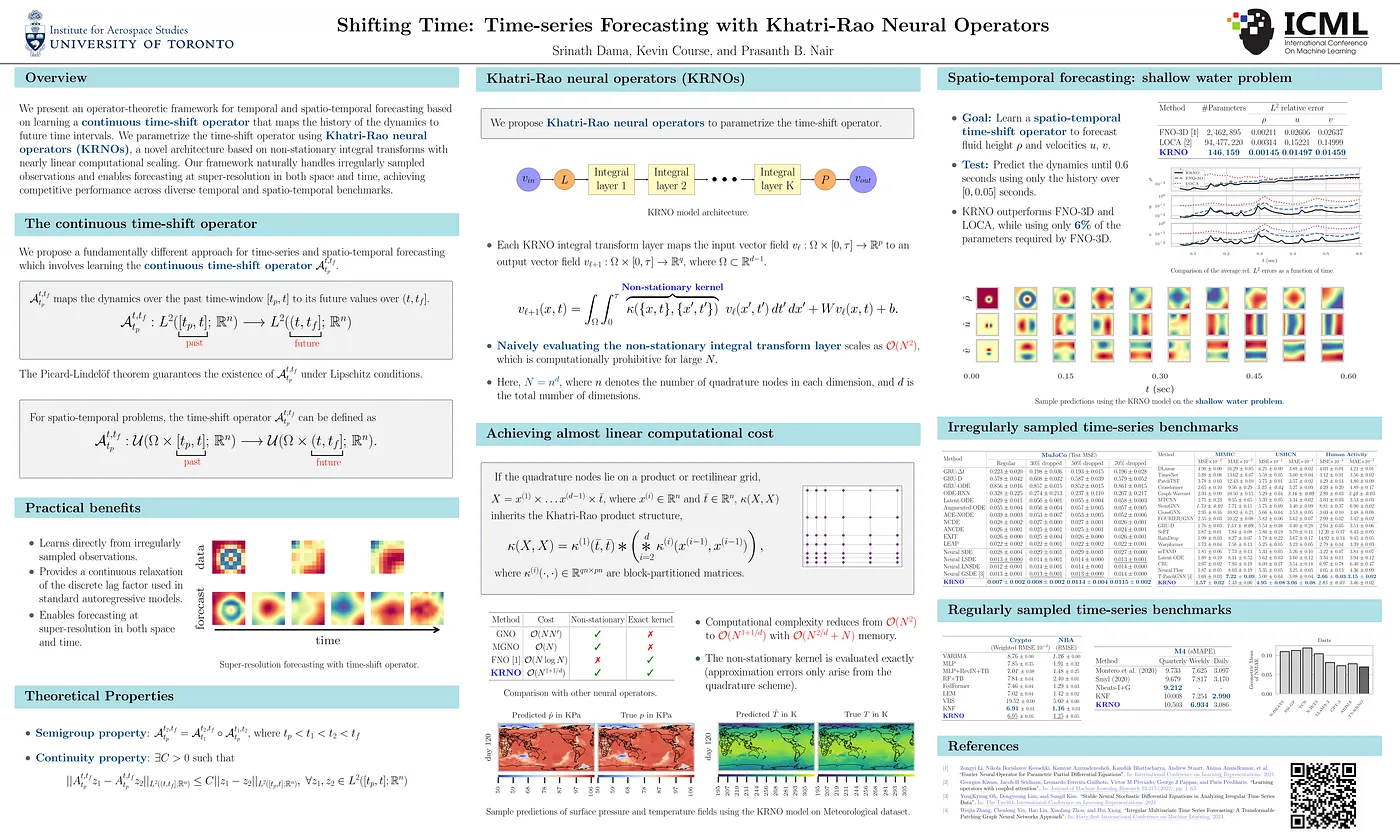

| Shifting Time: Time-series Forecasting with Khatri-Rao Neural Operators | Srinath Dama | Modeling Dynamical Systems & Time-Series |

| Optimization for Neural Operators can Benefit from Width | Pedro Cisneros-Velarde | Neural Operators |

| Accelerating PDE-Constrained Optimization by the Derivative of Neural Operators | Ze Cheng | Neural Operators |

| CoPINN: Cognitive Physics-Informed Neural Networks | Siyuan Duan | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Sub-Sequential Physics-Informed Learning with State Space Model | Chenhui Xu | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Causal-PIK: Causality-based Physical Reasoning with a Physics-Informed Kernel | Carlota Parés Morlans | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Physics-Informed DeepONets for drift-diffusion on metric graphs: simulation and parameter identification | Jan Blechschmidt | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Refined generalization analysis of the Deep Ritz Method and Physics-Informed Neural Networks | Xianliang Xu | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Physics-Informed Generative Modeling of Wireless Channels | Benedikt Böck | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Physics-informed Temporal Alignment for Auto-regressive PDE Foundation Models | Congcong Zhu | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Physics-Informed Weakly Supervised Learning For Interatomic Potentials | Makoto Takamoto | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Calibrated Physics-Informed Uncertainty Quantification | Vignesh Gopakumar | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Near-optimal Sketchy Natural Gradients for Physics-Informed Neural Networks | Maricela Best Mckay | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| A Physics-Informed Machine Learning Framework for Safe and Optimal Control of Autonomous Systems | Manan Tayal | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Geometric and Physical Constraints Synergistically Enhance Neural PDE Surrogates | Yunfei Huang | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| PDE-Transformer: Efficient and Versatile Transformers for Physics Simulations | Benjamin Holzschuh | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| Neural Interpretable PDEs: Harmonizing Fourier Insights with Attention for Scalable and Interpretable Physics Discovery | Ning Liu | Automated Scientific Discovery |

| From Uncertain to Safe: Conformal Adaptation of Diffusion Models for Safe PDE Control | Peiyan Hu | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| Holistic Physics Solver: Learning PDEs in a Unified Spectral-Physical Space | Xihang Yue | Neural Operators |

| Unisolver: PDE-Conditional Transformers Towards Universal Neural PDE Solvers | Hang Zhou | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| MultiPDENet: PDE-embedded Learning with Multi-time-stepping for Accelerated Flow Simulation | Qi Wang | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Toward Efficient Kernel-Based Solvers for Nonlinear PDEs | Zhitong Xu | Neural Operators |

| Active Learning with Selective Time-Step Acquisition for PDEs | Yegon Kim | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| PINNsAgent: Automated PDE Surrogation with Large Language Models | Qingpo Wuwu | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| PDE-Controller: LLMs for Autoformalization and Reasoning of PDEs | Mauricio Soroco | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| M2PDE: Compositional Generative Multiphysics and Multi-component PDE Simulation | Tao Zhang | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Transolver++: An Accurate Neural Solver for PDEs on Million-Scale Geometries | HUAKUN LUO | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| Zebra: In-Context Generative Pretraining for Solving Parametric PDEs | Louis Serrano | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| Mechanistic PDE Networks for Discovery of Governing Equations | Adeel Pervez | Automated Scientific Discovery |

| Curvature-aware Graph Attention for PDEs on Manifolds | Yunfeng Liao | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| PEINR: A Physics-enhanced Implicit Neural Representation for High-Fidelity Flow Field Reconstruction | Liming Shen | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Efficient and Scalable Density Functional Theory Hamiltonian Prediction through Adaptive Sparsity | Erpai Luo | Physics-Informed Learning (PINNs) |

| Neural Discovery in Mathematics: Do Machines Dream of Colored Planes? | Konrad Mundinger | Automated Scientific Discovery |

| QuanONet: Quantum Neural Operator with Application to Differential Equation | Ruocheng Wang | Neural Operators |

| Discovering Physics Laws of Dynamical Systems via Invariant Function Learning | Shurui Gui | Automated Scientific Discovery |

| Inverse problems with experiment-guided AlphaFold | Sai Advaith Maddipatla | Automated Scientific Discovery |

| Discovering Physics Laws of Dynamical Systems via Invariant Function Learning | Shurui Gui | Automated Scientific Discovery |

| Symmetry-Driven Discovery of Dynamical Variables in Molecular Simulations | Jeet Mohapatra | Automated Scientific Discovery |

| Skip the Equations: Learning Behavior of Personalized Dynamical Systems Directly From Data | Krzysztof Kacprzyk | Modeling Dynamical Systems & Time-Series |

| Chaos Meets Attention: Transformers for Large-Scale Dynamical Prediction | Yi He | Modeling Dynamical Systems & Time-Series |

| Transformative or Conservative? Conservation laws for ResNets and Transformers | Sibylle Marcotte | Foundation Models & Large-Scale Architectures |

| Thermalizer: Stable autoregressive neural emulation of spatiotemporal chaos | Chris Pedersen | Modeling Dynamical Systems & Time-Series |

Now, let’s talk about some papers that looked like a good contribution in this field and explain their work:

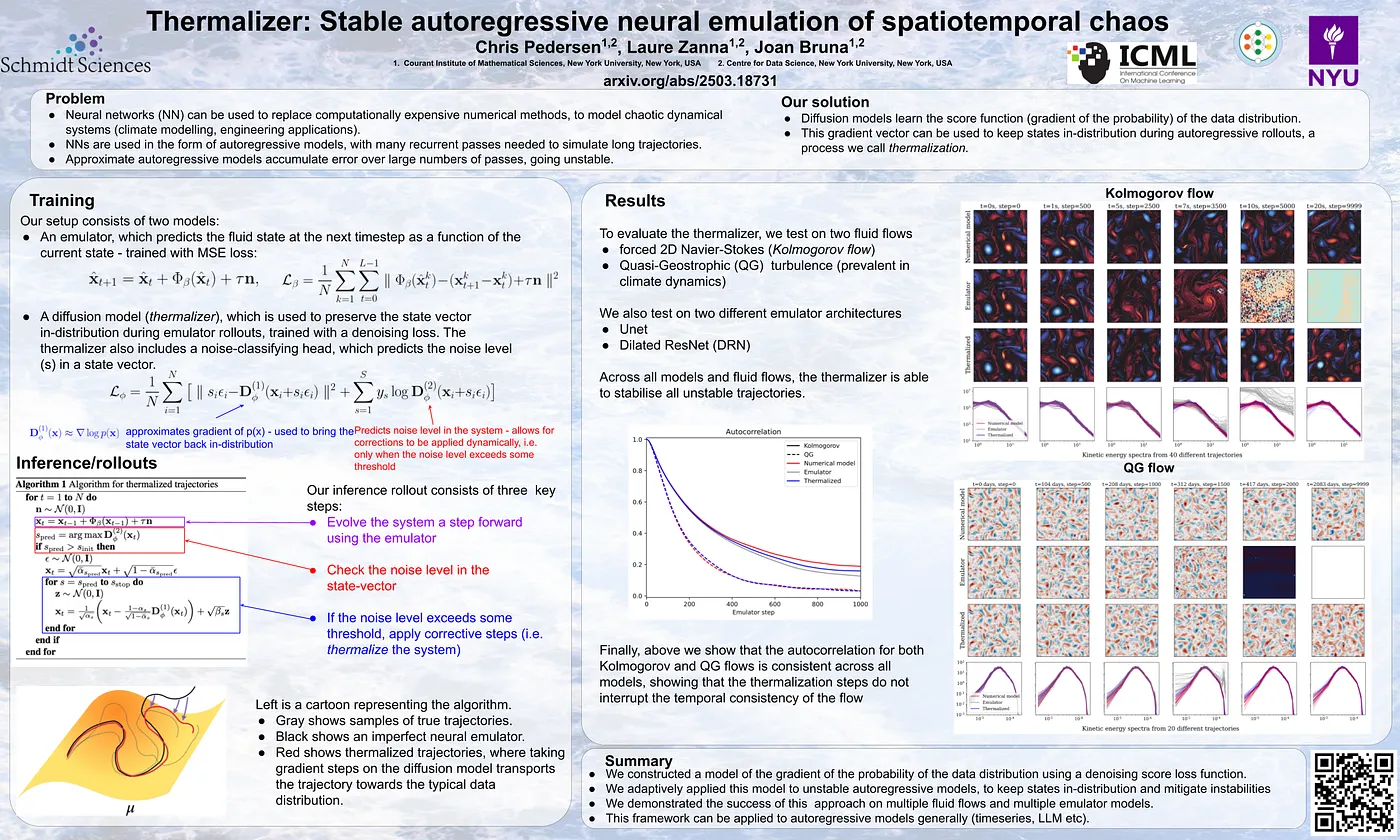

Thermalizer: Stable autoregressive neural emulation of spatiotemporal chaos [1]

This paper mostly focused on the inference time, where we want to make our forecasting, but there exists a major problem called cumulative error. This mostly happens on autoregressive prediction. Thermalizer is a new approach that tries to train a secondary model, alongside the main model, by learning dynamical features of the system, and keeps the predictions in the right direction based on the physics of the problem. It helps to correct errors and back the prediction to the right trajectory, after making our prediction steps. Find more at arxiv.

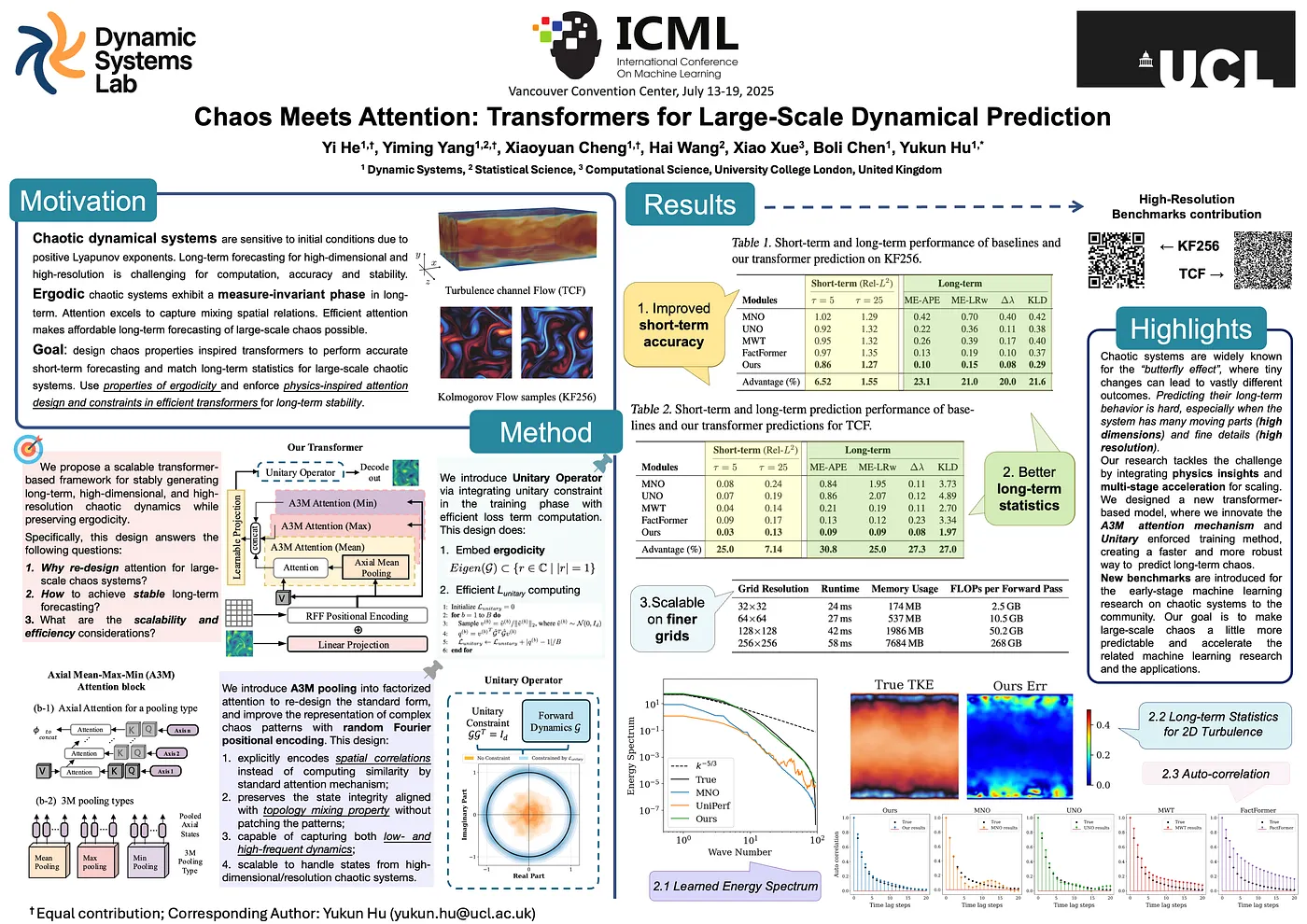

Chaos Meets Attention: Transformers for Large-Scale Dynamical Prediction [2]

This paper introduces a new deep learning framework that leverages the power of Transformer architectures to perform large-scale, long-term forecasting of chaotic dynamical systems. The authors propose a method that combines a parallel-in-time, auto-regressive training scheme with a novel attention mechanism designed to capture the complex spatiotemporal dependencies inherent in chaotic behaviour. Their model aims to overcome the limitations of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and other approaches, which often struggle with error accumulation during prediction. Find more at arxiv.

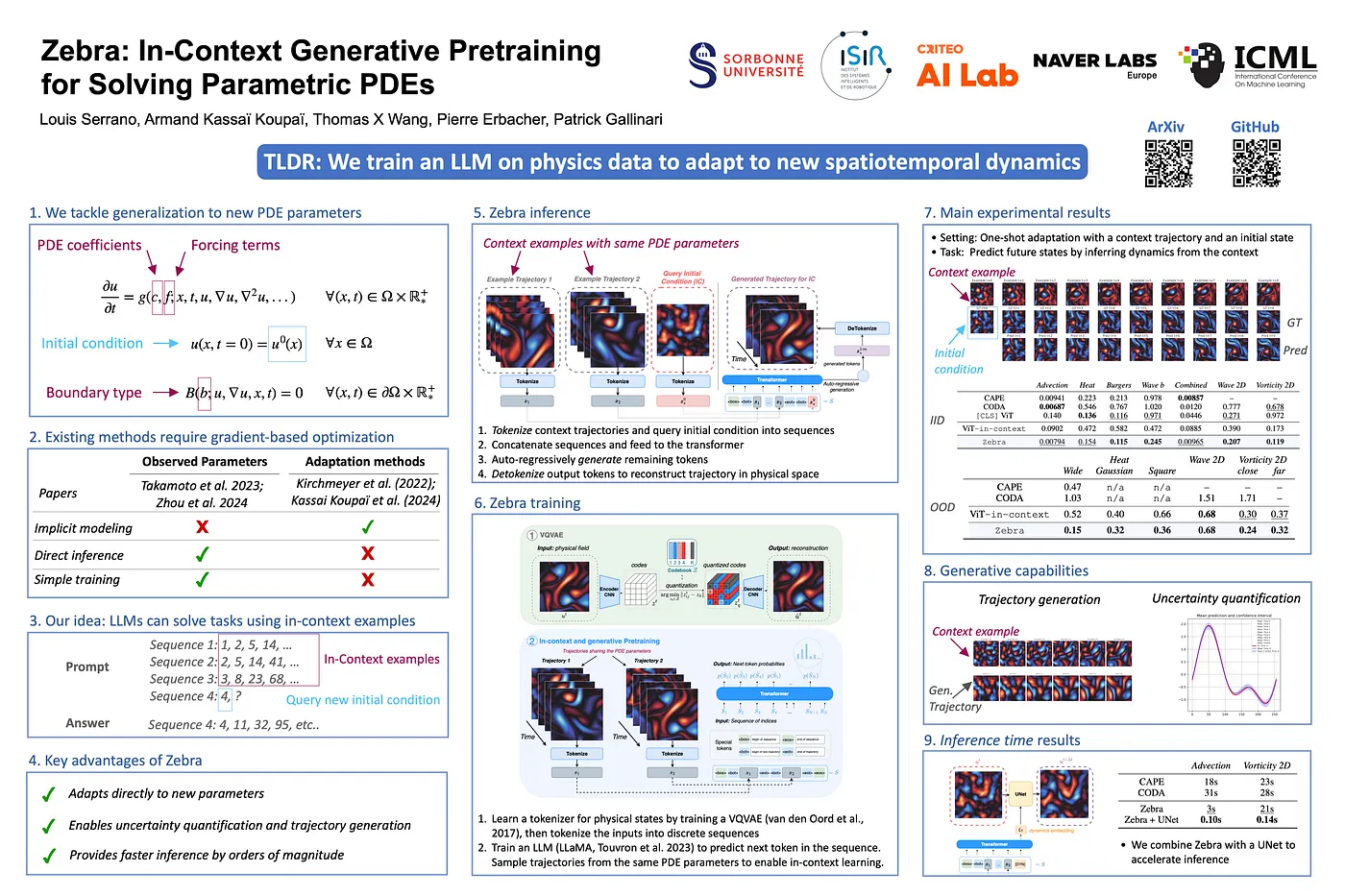

Zebra: In-Context Generative Pretraining for Solving Parametric PDEs [3]

This is a new kind of approach to leverage the in-context learning in natural language processing, but now in PDEs and dynamical systems prediction. Here we train a transformer model with a few examples of a specific PDE (e.g. Navier-Stokes), then try to predict the next steps of a trajectory, by providing the first few steps of it. This paper tries to focus on interpolation and in-bound prediction, based on systems that the model was trained on, but for future work, it could be applied to out-bound prediction, or even train a foundational model for different PDEs and have a multi-system surrogate. Find more at arxiv.

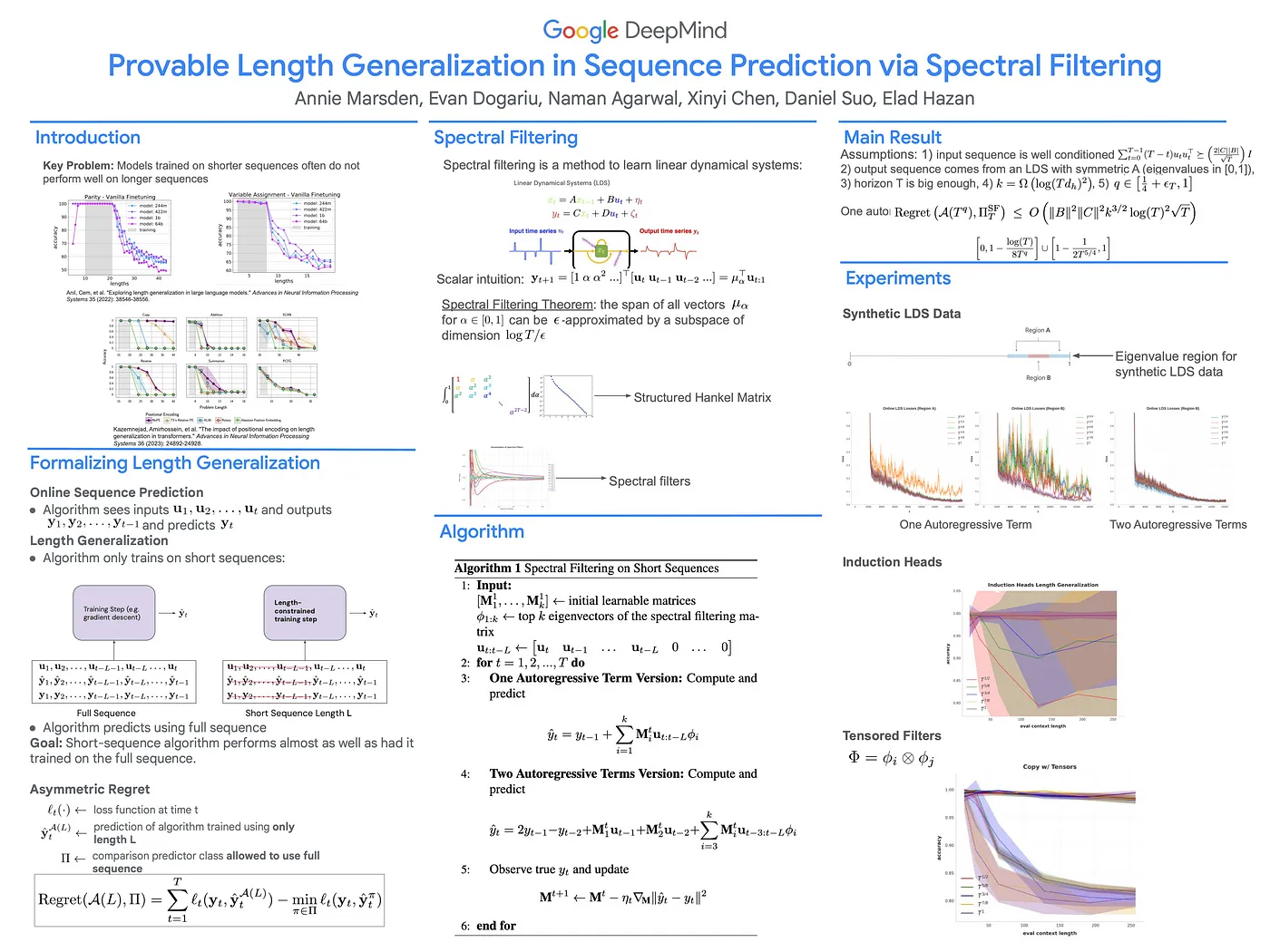

Provable Length Generalization in Sequence Prediction via Spectral Filtering [4]

A great contribution to solving linear dynamical systems via data-driven methods for learning a spectral filter for the system, to gradient-based learning and achieving length generalization for linear dynamical systems. This paper also introduces “tensorized spectral filter” and provides algorithms that provably generalize. During the presentation, most people asked about the relationship between this method and the Koopman Operator method. The Koopman operator method learns a global model of the system’s underlying dynamics, while this paper’s spectral filtering method learns a direct predictive function for the output sequence by minimizing regret, without needing to model the entire system. Find more at arxiv.

A Bregman Proximal Viewpoint on Neural Operators [5]

In this paper, we see one step forward in the theory of neural operators. A. Mezidi et al. introduced a new component at each layer (from a practical point of view), which is the inverse of the activation function, which adds an extra non-linearity to the learning process. Theoretically, this method connects activation functions to Bregman proximity operators, where the specific activation is determined by the choice of regularization. This method resulted in improved performance in deeper models by allowing layers to more easily reduce to an identity mapping, and ending up with a more sparse weight set. Find more at paper.

Shifting Time: Time-series Forecasting with Khatri-Rao Neural Operators [6]

A good contribution from the University of Toronto in forecasting that learns a continuous time-shift operator to map a system’s history to its future values. Authors introduce a new architecture, Khatri-Rao Neural Operators (KRNOs), which is nearly linear computational scaling. This framework naturally handles irregularly sampled observations and enables super-resolution forecasting in both space and time. Find more at paper.

SAND: One-Shot Feature Selection with Additive Noise Distortion [7]

This is a little bit off topic and a more general contribution, but we found it helpful. SAND (Selection with Additive Noise Distortion) is a simple feature selection method which tries to select the most effective features at every start of the learning workflow. In addition could be placed at any other points of the flow as well. Its main contribution is a non-intrusive input layer that applies trainable gains and weighted Gaussian noise to each feature, governed by a normalization constraint that forces the sum of squared gains to equal the desired number of features, k. Find more at arxiv.

References

[1] Pedersen, Chris, Laure Zanna, and Joan Bruna. “Thermalizer: Stable autoregressive neural emulation of spatiotemporal chaos.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.18731 (2025).

[2] He, Yi, et al. “Chaos meets attention: Transformers for large-scale dynamical prediction.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.20858 (2025).

[3] Serrano, Louis, et al. “Zebra: In-context and generative pretraining for solving parametric pdes.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.03437 (2024).

[4] Marsden, Annie, et al. “Provable Length Generalization in Sequence Prediction via Spectral Filtering.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.01035 (2024).

[5] Mezidi, Abdel-Rahim, et al. “A Bregman Proximal Viewpoint on Neural Operators.” International Conference on Machine Learning. 2025.

[6] Dama, Srinath, Kevin Course, and Prasanth B. Nair. “Shifting Time: Time-series Forecasting with Khatri-Rao Neural Operators.” Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning.

[7] Pad, Pedram, et al. “SAND: One-Shot Feature Selection with Additive Noise Distortion.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.03923 (2025).